Financial crashes are rare events, but these rare events have direct impact on any risk assessment, the pricing of risk assets, and portfolio structuring. The impact of these rare events is through the probabilities that investor may associate with them. If the price of any security is the discounted value of future prices times their probability, a higher weight for negative events will pull down expected prices.

There can be a significant impact on performance if the probability assessments for rare events are wrong. If rare events are under appreciated or given too low a probability, risky assets may be over-represented. Similarly, if a risk assessment is given too high an assessment, money will be left on the table because risky assets will be under-represented in the portfolio.

A paper written in last year is especially relevant in today's market where the talk of a market crash seems to be increasing with every movement up in price. See "Crash beliefs from investor surveys", by William Goetzmann, Dasol Kim, and Robert Shiller. This paper uses time series survey information from a simple question:

The results show that investors place, on average, a probability of approximately 20% to the chance of a rare case event in the next six months. This is an odd assessment given the actual probabilities are more likely to be less than 1 percent. It seems too high relative to actual occurrences.

The results show that investors place, on average, a probability of approximately 20% to the chance of a rare case event in the next six months. This is an odd assessment given the actual probabilities are more likely to be less than 1 percent. It seems too high relative to actual occurrences.

So what could cause this crash assessment to be so high? The authors conjecture that it is associated with news about crashes. If there is more news or reporting on bust, crashes, and bad news, there will be a higher assessment by investors that they will occur. This could be part of a bias by investors. Without sarcasm, if it does not seem rational, it must be a behavioral bias. The behavioral bars of availability would suggest that if there is more information available about a negative event, there will be a greater likelihood that investors will increase there probability of a crash.

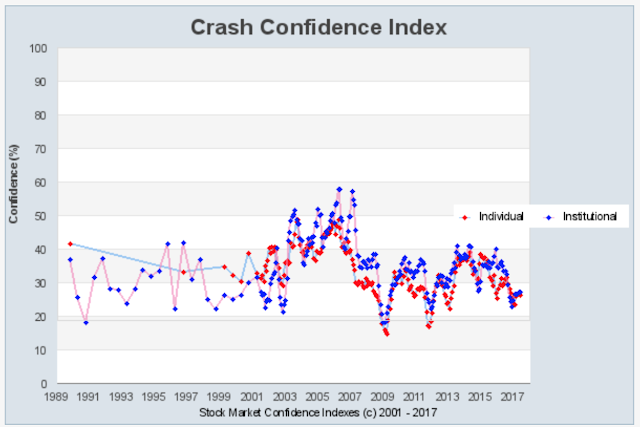

The current numbers from the Yale International Center for Finance show that crash risk is higher than expected relative to the actual data, but is lower than the expected probabilities over the last few years. It will be interesting to see if this number increases quickly in the fall.

Crash risk has been high throughout the post Financial Crisis period, yet there has not be a crash. There have been mini or flash crashes based on electronic trading, yet nothing has met the criteria described in the question. Could the fear of a crash been keeping investors on the sidelines? The research question that has to be addressed is translating what investors say into what they will do. Additionally, as this paper points out, confidence can be swayed by news and opinions of others. This feedback loop is critical for understanding market behavior.